Life Lessons from the World’s Top Hostage Negotiator — with Gary Noesner

Recent Conversations

Gary Noesner, FBI’s Former Chief Hostage Negotiator and the first ever Chief of the bureau’s Crisis Negotiation Unit, has mastered the art of defusing conflict in the midst of volatile and emotionally charged situations. He also led the FBI in reshaping and transforming their response strategies to crisis and high-stakes conflicts.

During his tenure, Gary investigated and negotiated some of the most high-profile hostage situations including middle east hijackings, prison riots, militia standoffs, kidnappings, and embassy takeovers.

His book “Stalling for Time, My life as an FBI Hostage Negotiator” served as the framework for the popular Netflix mini-series Waco as well as its sequel, Waco, The Aftermath, which debuted on Showtime on April 16th, 2023.

I’ve had the pleasure of getting to know Gary over the past year. He’s not only a badass Peacemaker, but also a warm, soulful and kind human with great energy and deep curiosity.

In this conversation, Gary reveals the most valuable life lessons he learned on the job and the ways we can apply them to our everyday lives.

SAVVY Takes

Background about Negotiation at the FBI

For many years, the FBI and police departments across the U.S. approached negotiation with criminals as a bargaining interaction, a quid for pro. In the case of a hostage negotiations, for example, the FBI would exchange food for a hostage.

In the 1980s, the New York City Police Department realized that a big part of their work was centered on crisis intervention and management.

Many cases involved dealing with emotionally intense conflicts, often with enraged citizens who had experienced recent life setbacks or challenging events. Perhaps they were fired from a job, had a difficult break up with a significant other, or an intense argument with a family member or neighbor.

Investigations into these cases revealed that most perpetrators didn’t have a specific goal in mind when acting out or committing crimes. Their actions were driven by intense emotional states: a response to their new situation and reality.

With guidance from the mental health community, the FBI set out to evolve its approach to crisis intervention. Once developed, the bureau invested in training law enforcement teams worldwide on this new approach. Gary became one of only two full-time negotiators at the FBI in 1990.

The key idea was to use communication skills as the primary way to resolve conflict. This evolution redefined the concept of negotiation at the FBI and Police Departments across the country.

The New Approach to Negotiation and Conflict Resolution

FBI’s evolved approach led with emotional intelligence, and centered on active listening, empathy, and sincere communication.

It quickly proved its effectiveness, gained widespread acceptance, and replaced the previous authoritative approach to conflict management.

Gary remarks: “There are still events that end very tragically, despite the effort that we put into it, but we have learned that if we’re slow, patient and thoughtful, it really helps to lower the tension, and deescalate the situation. And that allows us to get to a place where both parties are thinking more clearly, and make better decisions. The success rate of this empathetic approach is in the mid to high 90 percentiles.”

Gary believes that this transformation is the most important development in law enforcement during his lifetime. “If these approaches work in what historically has been a very adversarial relationship between perpetrators, or even dangerous criminals and police officers, we certainly should be able to apply these skills during family disputes or business transactions.”

Gary shared many interesting stories and anecdotes. I cannot do them justice here, so I highly recommend listening to the actual conversation. Below are the highlights of the essential lessons he shared.

Emotional Intelligence: The Most Essential Life Skill

Our emotions are the powerful drivers of our actions. So, emotional self-awareness, self-regulation, and empathy are essential to conflict and crisis management.

Emotional Self-awareness and Regulation

Emotional self-awareness connects us to our internal experiences and helps us identify and understand our own triggers, so we can manage their emotional charge.

This practice allows us to resist emotionally driven impulses and reactions during highly tense or stressful situations.

And in turn, we can keep a more open perspective, tap into the needs of each circumstance and express ourselves in healthy and effective ways.

These skills take more effort for some of us than others.

And it’s important to keep up with the work and continue to reinforce what we’ve learned in preparation for the inevitable: life disruptions, changes, and challenges that bring on all the feels.

Our mission, first and foremost, is to lower our own emotional charge to the best of our ability. Longstanding, married couples have probably learned, for example, that when you get really angry with each other, it might be best to walk away from it for a while. And settle down. Because you can say things in the heat of battle that can be very hurtful and can create further damage down the road. Or just perpetuate the ongoing crisis.

Gary Noesner

Empathy

Empathy is the foundational to mutual understanding, effective communication, and genuine connection, especially when managing conflict and challenging conversations. Gary emphasized the importance of the following points:

- Listen with intention: Active listening helps us tap into other people’s emotional states, and better understand their experiences, and real needs. To uncover the underlying motivations, we must dig deeper, beyond what is explicitly communicated or demanded.

- Acknowledge the other side’s concerns and challenges: This de-escalates intense, emotionally charged conversations and reduces defensiveness.

- Demonstrate your understanding: Restate their points of view in your own words to validate your understanding. “We can’t influence others without understanding what drives them.’” Gary explains. “We earn the right to be of influence. And we earn that right by listening and understanding. And we don’t just say we understand. We prove it. We demonstrate it by paraphrasing or repeating what the other says.”

Relationships are Everything

Focus on building rapport and trust. They are vital to your ability to truly influence.

- Be upfront, honest and respectful: “I had a pretty good sense of humor and people always expected a very dry, somber FBI agent, with no sense of humor,” Gary remarked. “And when you’d be down to earth and let your hair down as it were, it surprised people and helped open up opportunities to communicate and go from there.”

- Ask probing and open-ended questions: This gives the other side the space to express their thoughts, feelings and perspectives, which in turn sheds mor light on their true needs and motivations.

- Find points of similarity and connection: Commonalities make us feel at ease, lower our resistance to others, and encourage genuine interaction.

They also make us more likable. “We are social animals and we have to learn how to engage with each other. As humans, everything is about relationships. And relationships form as the result of our interactions with each other,” Gary explains. “We really don’t give up anything by showing our human side.”

His advice is to focus on building relationships one interaction at a time. “Successful relationships and influence require strong interpersonal skills. When others trust us, whether it’s our friends, boss or partner, they will be more open to our suggestions, or alternative ways of doing things.”

He demonstrated this point with an insightful story.

“The FBI was trying to arrest this bank robber, a fugitive. And they surrounded his house. The guy started threatened to kill anybody that comes in. The house is surrounded, with lots of police officers there. And all of this was taking a long time.”

And as it turns out, in addition to being a part-time bank robber, he was also a carpenter. The negotiator, knowing that this guy is a carpenter, begins to ask him how to build a shed that the agent wants to build behind his own house.

And the guy automatically goes right into his. professional background. He starts to ask about the size (how big does it need to be?) and the materials he wants to use. And they talk for an hour or so about building this shed.

Meanwhile, the commander is frustrated and waiting to get this resolved and asks why he’s there talking to the guy about building a shed.

But what was going on there?

This highly educated FBI agent was talking with someone who had far less formal education. But he had a specific skill set that the agent didn’t possess, and respected. This situation gave the agent an opportunity to create rapport, and engage in a positive way.

And at this point, they had already built a virtual shed in their together, and the guy said he was ready to come out.”

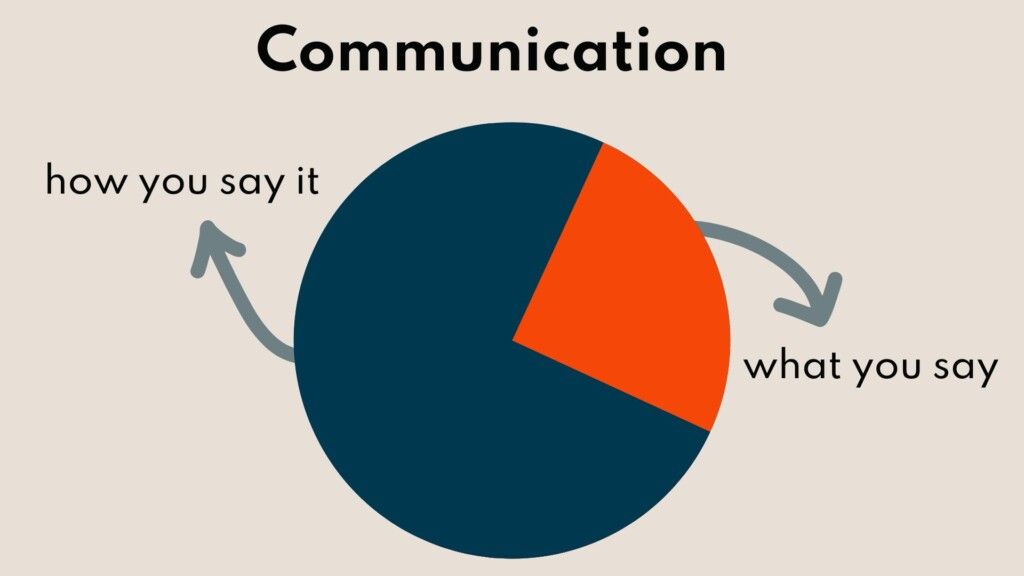

It’s not just what you say, but how you say it: Words and language matter. And yet they’re only one part of the communication puzzle.

Our tone, energy, body language and perceived personality greatly impact our message. In order to continuously improve the hostage negotiation team’s techniques, Gary regularly asked hostage takers to describe the specific interaction or words that led to their surrender.

“Their answer was always the same.” Gary revealed. “They didn’t remember what I said, but liked the way I said it, or communicated with them.”

Another of Gary’s stories involved a police officer from a small town in Alabama who was severely disabled after being wounded. He was placed on retirement while still in a coma at the hospital.

Once he awoke, he was angry. He criticized the department for rushing to judgement and cheating him out of his pension. Armed with a gun, he went to the mayor’s office and held him captive.

Gary and his team were called in to handle this delicate hostage negotiation. As the team engaged him and asked questions, it was clear that his pension, while important and demanded, wasn’t the hostage taker’s top priority.

Rather, his anger was fueled by the belief that his reputation had been destroyed. His real desire was to regain his standing in his community.

If you listen carefully, you can move beyond the stated demands or wants and desires and determine what’s really needed. You just don’t identify that with the blink of an eye or a snap of a finger. You have to invest the time and energy into listening and asking probing, open-ended question to try to clarify points and issues. And you may find that very often, just the mere fact of having someone listen to them for the first time, perhaps in their lives, is itself the solution to many of the problems.

Gary NOEsner

I was moved by the revelation of this powerful, universal truth.

Most of our “bad” and destructive behaviors are rooted in frustration, anger, and deep pain. All because our deepest needs – to feel heard, seen, and understood – remain unmet.

And we have no idea how to end our pain, or hurt less. So, we act out our anguish, especially if we can’t find anyone to listen to us, or acknowledge it.

For most conflicts Gary managed over the years, whether it was a hostage negotiation, a violent prison riot, or an office dispute, the inciting actions stemmed from a deep need. The need to feel heard.

Oftentimes , Gary was the first person ever to actually listen. To acknowledge their concerns. And to ensure their point of view was understood.

This truth is soooooo powerful.

I want to believe that with the revelation of this truth, we will all be able to engage with each other with more understanding and empathy.

But I also know that it’s much more complicated.

This conversation has inspired me to share this powerful truth more broadly.

Maybe each of us can play a small part in a shifting the culture towards one with more connection and less pain.